Reasons and Decision: In the Matter of Edward Furtak et al.

IN THE MATTER OF THE SECURITIES ACT,

RSO 1990, c S.5

- AND -

IN THE MATTER OF

EDWARD FURTAK, AXTON 2010 FINANCE CORP., STRICT TRADING LIMITED, RONALD OLSTHOORN, TRAFALGAR ASSOCIATES LIMITED, LORNE ALLEN AND STRICTRADE MARKETING INC.

REASONS AND DECISION

(Section 127 of the Act)

|

Hearing: |

May 9-13, 16, 18, 27 and 30, 2016 |

||

|

|

June 10, 2016 |

||

|

|

July 6 and 7, 2016 |

||

|

|

October 5 and 6, 2016 |

||

|

|

|||

|

Decision: |

November 24, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Panel: |

Janet Leiper |

-- |

Chair of the Panel |

|

|

D. Grant Vingoe |

-- |

Vice-Chair |

|

|

AnneMarie Ryan |

-- |

Commissioner |

|

|

|||

|

Appearances: |

Catherine Weiler |

-- |

For Staff of the Commission |

|

|

Yvonne B. Chisholm |

|

|

|

|

Christina Galbraith |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Julia Dublin |

-- |

For the Respondents |

REASONS AND DECISION

I. INTRODUCTION

[1] On March 30, 2015, Staff of the Ontario Securities Commission issued a Statement of Allegations pursuant to section 127 of the Securities Act{1} (the Act) against the Respondents. According to the Allegations, the Respondents variously violated Ontario securities laws by:

a. engaging in illegal distributions of securities, contrary to subsection 53(1) of the Act (all Respondents);

b. engaging in or holding themselves out as engaging in trading in securities without registration, contrary to subsection 25(1) of the Act (Lorne Allen, Strictrade Marketing Inc. (SMI), Edward Furtak, Axton 2010 Finance Corp. (Axton) and Strict Trading Limited (STL));

c. making misleading statements in contracts entered into with investors, contrary to subsection 44(2) of the Act (Furtak and STL);

d. violating several provisions of National Instrument 31-103 -- Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations (Trafalgar Associates Limited (TAL) and Ronald Olsthoorn);

e. failing to comply with Ontario securities laws as directors and officers, contrary to section 129.2 of the Act (Furtak, Olsthoorn and Allen);

[2] The Commission conducted a hearing into the merits of these Allegations over the course of 13 hearing days. Furtak and Olsthoorn attended and testified during the hearing. Allen did not appear, although he was represented at the hearing by counsel, as were the other Respondents.

[3] For the reasons that follow, we find that the allegations made by Staff have been established on a balance of probabilities, except for the allegation that Respondents Furtak and STL made misleading statements in contracts entered into with investors, contrary to subsection 44(2) of the Act.

II. BACKGROUND

A. The Strictrade Offering Components

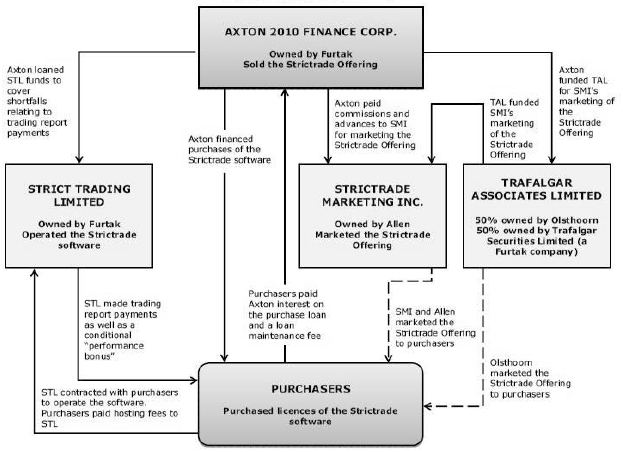

[4] The Respondents marketed and sold the "Strictrade Offering,"{2} a package of agreements in which third parties purchased, and financed, licences of the Strictrade software, in $10,000 units, from Furtak's company, Axton. Participants received a licence certificate granting them the ability to use the Strictrade software "up to a maximum of $50,000 trading capital per $10,000 of License Fee." The purchase of the software licence was financed by Axton itself and purchasers signed a promissory note in favour of Axton for the purchase amount of the licences. Purchasers simultaneously contracted with another of Furtak's companies, STL, the "customer" who was intended to operate the software by trading futures contracts using the "trading report" instructions generated by the software.

[5] The contract with STL required that the software be operated outside of Canada. STL would operate the software at their premises and provide the computer equipment, internet connectivity and any third party software needed to operate the Strictrade software. STL would also install, operate and monitor the operation of the software and perform necessary upgrades.

[6] Purchasers were required to purchase a minimum licence unit valued at $10,000 and to pay 15% in fees in advance annually: interest on the purchase loan, at 9.5%, and a 1% loan maintenance fee paid to Axton and an annual 4.5% software "hosting fee" paid to STL. These fees and interest payments were payable in advance in respect of each succeeding year. No payment of the principal was included in these amounts.

[7] In return, purchasers received annual "trading report payments" based on STL's use of the software. Use of the software for this purpose meant the receipt of trading signals provided by the software, whether or not STL actually effected such trades. These were fixed returns ($1.00 per trade report to a maximum of $950 on a $10,000 investment, or 9.5%, to be increased by 4.25% of the previous year's amount in each succeeding year). The payments to participants were not due until the participants made their next year's advance payments of interest and fees, creating a lag between the payments made and income received by purchasers.

[8] Purchasers did not share in any profits or losses as a result of the use of the trading software by STL. This was promoted as a benefit because only STL, the customer, would be exposed to market volatility and risk, or as one promotional slide put it:

So Whether The Trading Manager Makes Money or Loses Money Trading In The Market ... Your Business Earns Revenue!

[9] The annual fees and interest paid by the purchasers to Axton and STL exceeded the trading report payments the purchasers received (all purchasers uniformly received the contractual maximum) both because the purchasers were required to pay the amounts due from them a year in advance and because of the quantum of the interest and various fees payable.

[10] One additional payment to participants was possible under the agreement. Purchasers who remained in the program for five years were entitled to a "Software Performance Bonus." Although it was called a "Performance Bonus," it was not connected to trading performance. The Bonus was calculated as 60% of the trading report payments made to date. Payment of the Bonus would trigger the termination of the program.

[11] A $10,000 licence that earned the maximum $950 in annual trading report payments, with a 4.25% increase annually, held for five years, means that a participant would receive a Bonus equal to 60% of $5,171.28, or $3,102.77. This means that over the life of the program, such a participant would, assuming that the fifth year payment is made following the termination of the licence, receive revenue of $8,274.00 from the trading report payments and the Bonus.{3} This hypothetical licensee would pay STL and Axton a total of $7,500 over the term of the scheme, resulting in a gain of $774.04 after the Bonus payment is made and the licensee is out of the program.

[12] The marketing of the Strictrade Offering focused on the benefits to be had from deducting business costs and depreciation of the software, as well as potentially utilizing other tax deductions. These calculations were included in the spreadsheets Olsthoorn created to show to potential buyers. The promotional slides referred to the specific tax considerations and to the "AFTER TAX PROFIT" available to a person with a 40% tax rate.

B. The Strictrade Promoters

[13] On February 24, 1994, TAL was incorporated in Ontario. In August 2011, TAL was registered as an exempt market dealer. Olsthoorn owned 50% of TAL, and the other 50% was held by Trafalgar Securities Limited, another of Furtak's companies, making Furtak the 50% beneficial owner of TAL.

[14] Furtak founded Axton in 2010 and STL in 2012. Both were incorporated in the British Virgin Islands. Furtak developed the software that was the basis for the licences sold in the Strictrade Offering. He arranged for his business associates, Olsthoorn and Allen, to assist with the promotion of the Strictrade Offering beginning in 2012.

[15] During 2010 and 2011, Furtak, Olsthoorn and Allen developed the structure of the Strictrade Offering and planned a marketing strategy. Furtak drafted most of the agreements in consultation with a lawyer.

[16] On January 1, 2012, Allen incorporated SMI in Canada. SMI, Allen and Olsthoorn all received compensation for their marketing activities for the Strictrade Offering. Furtak testified that SMI was created to market the Strictrade Offering because the Respondents believed that they were not marketing a security. They said that they did not want to use TAL to market the Strictrade Offering because it was a registrant who was a named defendant in a class action suit, which could be discovered by a web search. The licensees were asked to make their cheques out to SMI for their first year's prepaid interest and loan maintenance fees.

[17] Allen, Axton, STL and SMI have never been registered with the Commission. Furtak was registered in 1992-1994 and was an approved shareholder of TAL, an exempt market dealer, since August 19, 2011. Furtak was not registered to sell securities during the Strictrade Offering marketing period.

[18] Olsthoorn was registered as the Ultimate Designated Person (UDP) and Chief Compliance Officer (CCO) of TAL.

C. The Marketing of the Strictrade Offering

[19] Beginning in January of 2012, Allen and Olsthoorn gave presentations on the Strictrade Offering to financial professionals in various cities across Canada. Olsthoorn also gave presentations in Las Vegas, United States. All told, Allen and/or Olsthoorn gave 43 group presentations to over 1,000 individuals between January 2012 and October 2013. Allen also gave 60-80 individual presentations to accountants, life insurance agents and mortgage brokers.

[20] The Respondents operated according to a Master Distributor Agreement between Axton and SMI, which provided for the payment of commissions and advances to SMI for the marketing of the Strictrade Offering. Axton agreed to fund the marketing by SMI through TAL, and when Olsthoorn began travelling to promote Strictrade, TAL paid his salary and expenses.

[21] Although Olsthoorn testified that TAL was not doing anything of significance in its marketing of the Strictrade Offering, TAL did the following:

a. shared its office space with SMI and Toronto Research and Trading, an entity that monitored the software for STL;

b. provided staff to do the bookkeeping and administrative paperwork for SMI including, corresponding with purchasers and arranging for trading report payments;

c. paid $328,000 to SMI in funds received from Axton to fund the marketing activities of SMI;

d. paid Olsthoorn's expenses and salary for travel to present the Strictrade Offering based on received expense forms; and

e. provided access to the TAL database of contacts for Olsthoorn's use in marketing the Strictrade Offering.

[22] The Panel was also presented with evidence that Olsthoorn's biography on the Pro-Seminars website noted him as "President of TAL" and as a "training and development specialist for distributors of Strictrade." Further, the agenda for a Pro-Seminar in August 2013 noted that Olsthoorn was from "Strictrade/Trafalgar Associates Limited" and would present an item entitled "Generating attractive net after-tax annual PROFITS for your client."

[23] The Respondents concede that no prospectus was filed or receipted. They assert that the Strictrade Offering did not involve the distribution of a security when marketed by Olsthoorn and others. As a result, the Respondents assert that TAL and/or Olsthoorn were right not to collect Know Your Client (KYC) information or to conduct a suitability assessment during the marketing of the Strictrade Offering. Olsthoorn testified that if he had done so, this would have been admitting that it was a security. He characterized the Strictrade Offering as an "alternative arrangement."

[24] Allen and Olsthoorn used slides and provided brochures to seminar attendees. A number of versions of the slides were filed at the hearing, all with essentially the same elements. The slides described the Strictrade Offering in terms that included:

"an opportunity to start your own business using computerized Trading Software and to profit from volatility in the financial markets"

and

"The Software is Hosted and Operated By a Professional Trading Manager -- Insulating You From Any Market Volatility, Risk and Operations."

[25] The Strictrade software licence was described as the foundation of the "Strictrade Business Model." The business opportunity for using the licences had "two easy steps." The first step was to finance the purchase of the licences on the terms offered. The second step was to sublicense the software to the professional trading manager, STL. Essentially, Furtak inserted a group of purchasers between his company, Axton, and his other company, STL, to use software he had developed to generate trading instructions. No business reason was provided for Axton and STL needing to contract with third party purchasers of the licences.

1. The References in the Marketing Materials to the "Independent Software Valuation"

[26] In 2011, Furtak retained an accounting firm, Wise-Blackman, now MNP, to conduct a valuation of a software licence with associated agreements, in which participants would pay a monthly hosting fee and receive a share of the profits and losses traded using the software (the 2011 Valuation).

[27] Furtak later used the results of this software licence valuation in the promotional materials developed for the Strictrade Offering. The presentation slides referenced an "Independent Software Valuation by Wise-Blackman now MNP," which the Respondents confirmed was the 2011 Valuation. A copy of the 2011 Valuation was not provided to prospective purchasers. The cover page of the 2011 Valuation was included in the promotional material, as was information about the credentials of the partners of MNP. One sentence was lifted from the body of the 2011 Valuation, which noted:

Based on and subject to the foregoing analysis and comments, and as outlined in this report, the estimated Fair Market Value of the License at the Valuation Date was $10,800.

[28] The 2011 Valuation report filed at the hearing included an opinion on the estimated fair market value of a licence to use STRICT trading software, purchased under a Trading Software License Agreement. This was not the licence that participants in the Strictrade Offering purchased. The 2011 Valuation evaluated historical simulated data provided by management (Furtak), which showed profits from the trading software between 2002 and 2011. These profits ranged from a low of 6.54% in 2010 to a high of 41.24% in 2008. The 2011 Valuation was based on an allocation of monthly profit or loss to licensees, less a monthly trading fee. MNP relied on the data provided by Furtak and did not independently verify this data. It applied a discount to expected shares of profits based on the fact that simulated data had been provided. The underlying licences being valued involved a share in the expected profits. However, Furtak continued to update this valuation by adjusting only for trading signals that the software continued to generate, regardless of actual trading, without any change in assumptions and without any additional verification or updating by MNP. The updated valuations were nonetheless continuously published on STL's website. Such valuations purported to provide a termination price at which Axton would repurchase the licences if the licensee exited the program, although such commitment was entirely an unsecured obligation of Axton.

[29] The 2011 Valuation did not consider a licences agreement in which participants were insulated from profits or losses and were paid a fixed rate of return via trading report payments. It made no mention of a Software Performance Bonus. Furtak testified at first that the valuators were aware of the entire transaction and structure but later said that they must not have considered the STL Services and Trading Report Sales Agreement (STL Services Agreement) to be relevant.

[30] The 2011 Valuation report noted that the opinion had been requested "solely for internal purposes and for Axton's management's use in financial planning." Restrictions were placed on its general circulation and publication or reproduction in whole or in part without express written consent from MNP.

[31] Both Olsthoorn and Furtak agreed that the 2011 Valuation was included in the presentation materials to lend credibility to the offering and to assure purchasers that they were getting something of value. The "value" was also used to provide assurance that if any purchaser chose to leave the scheme, they could "sell back" their initial investment at the base amount paid in order to avoid a claim for the principal on their loans from Axton.

2. Anticipated Tax Consequences

[32] The role of tax deductions in generating profit appears on a number of the promotional slides. For example, on the "Business Opportunity" slides, the business is described as "Simple to Manage-Only Requires An Annual Tax Filing" and claims that it "produces personal tax benefits." Later on in the presentation, a slide titled "Tax Considerations for Your Small Business" provided three tax aspects: the depreciation on the computer software, the interest on the money borrowed and the hosting fees as business expenses.

[33] The promoters also described how the participants could generate income from the Strictrade Offering. Allen said that all the participants had to do was "file a tax return, that's it." Olsthoorn said that from a "hands-on perspective" all the investors had to do "physically" was to make their annual payments and file a tax return. This was consistent with the representations made in the slides used at the presentations, including statements such as "Strictrade Provides An Opportunity To Operate A Business -- Trading Securities Without Any Personal Expertise Or Personal Time Commitment."

[34] The focus on the tax aspects of the scheme was necessary because there was little to be had in the way of profits from the enterprise for at least five years from the payments alone. It also necessitated the assurance that the "asset" at the core of the offering, the licence, had been independently valued. It had not. However, the evidence also demonstrated that any tax benefits were not generally worthwhile for those who were not in a 40% tax bracket.

[35] In an interview with Staff, Allen described the Strictrade Offering in these terms:

It's complicated and very difficult for even accountants to understand. But once they get it, it's a wonderful program. That's why no one actually sold one other than myself and Mr. Olsthoorn. That's it. We had to do all the work. It was too complicated for individuals to do it on their own.

D. The Purchasers of the Strictrade Offering

[36] Five purchasers of the Strictrade Offering testified at the hearing. Two of them had already terminated their involvement in the scheme. The others continued to pay the annual fees and receive trading report payments.

[37] The participants all signed the package of agreements described above with STL being the software user. None of the participants had seen the software, operated the software or was put forward as being capable of operating the trading software.

[38] As for their understanding of the scheme from the presentations they attended, every participant was motivated by some form of income or return. Some took money from a registered retirement saving plan (RRSP) (a "strategy" discussed in the presentations) to finance their payments for the Strictrade Offering.

1. Geraldine O

[39] Geraldine O, a 59-year-old nurse, said that she had limited understanding of the financial world. She attended one of Allen's presentations at her accountant's office. Ms. O found the details of the Strictrade Offering complex to understand. She was reassured by the statements in the brochure, such as "recession-proof" and "low levels of personal risk." Ms. O and her sister Moira O each purchased licences. Ms. O financed her purchase by withdrawing $10,000 from her RRSP. Ms. O saw the Strictrade Offering as "an opportunity to invest in a piece of software and everything was taken care of by somebody else."

[40] Ms. O believed that her initial investment was the only payment required, in part because the brochure read "no additional capital requirements." When she later realized that the contracts required annual payments, Ms. O and her sister terminated their involvement in the scheme.

[41] Three years after making her initial investment of $10,000, Ms. O received her trading report payment of $6,650. She did not know if she received any tax benefits from the scheme. Moira O received $4,500 from her $7,500 investment. Neither was entitled to any Software Performance Bonus because they had not stayed in the scheme for five years.

2. David D

[42] David D is a 75-year-old grocery clerk with a "fair" knowledge of investments. He had investments in a number of companies and a net worth that qualified him as an accredited investor. Mr. D's accountant introduced him to Allen, who he described as someone knowledgeable about computers with a good investment. After spending time with Allen to discuss the Strictrade Offering, Mr. D paid $75,000 and signed the contracts.

[43] Mr. D understood the Strictrade Offering as "just give them the money and they looked after everything and it was a good investment." He has paid $75,000 annually since entering into the agreement in May 2012 and received back approximately $50,000 on the anniversary, or recently, much later than the anniversary. He also claimed a tax deduction for the payments made each year, which has not been challenged.

3. Daniel G

[44] Daniel G is a 60-year-old life insurance agent registered with the Financial Services Commission of Ontario. His annual income was approximately $25,000 per year. He heard about the Strictrade Offering at a Pro-Seminar session given by Olsthoorn in September 2012 in Cambridge, Ontario.

[45] Olsthoorn met with Mr. G after a seminar in London, Ontario, to discuss the Strictrade Offering. Olsthoorn provided a set of projections that demonstrated profitability for a person in a 40% tax bracket. According to Mr. G, he told Olsthoorn he made $25,000 and that Olsthoorn said that the Strictrade Offering would still be beneficial for a person in a 20% or 24% tax bracket.

[46] According to Olsthoorn, Mr. G did not tell him his income was $25,000. Olsthoorn also said that he did not collect KYC information or have Mr. G fill out a form that would have shown his income. Olsthoorn later said that he assumed Mr. G had other sources of income in addition to that of his business.

[47] Mr. G chose to invest because his mutual funds in his RRSPs were not bringing a sufficient return. He believed that the Strictrade Offering did not seem to have any risk and that there would be positive income at the end of the six years, a time frame he decided would fit with his retirement plans. He believed the Offering would function like an investment in a mutual fund, changing in value over time.

[48] Mr. G did not understand that he was financing a purchase, believing that his initial payment of $15,000 was the purchase of the licence outright. He also was not aware that he would be required to pay this amount every year, believing that the phrase on the brochure "no additional capital requirements" meant that from then on he would receive returns and the investment would "pay for itself."

[49] Mr. G has struggled to make the annual payments. He has reduced his RRSP by over one-third to make the ongoing payments and said at one point, "This is killing me." He discussed leaving the program, but Olsthoorn told him he might be denied his tax deductions if he terminated early.

[50] Mr. G continues to pay $15,000 annually, receiving back approximately $10,000 annually under the terms of the agreement. He testified that "it hasn't turned out to be a good financial decision."

4. Georgina F

[51] Georgina F is a 59-year-old financial planner, licensed to sell insurance and mutual funds. She described her investment knowledge as excellent. Ms. F is an accredited investor because she is a registrant. Ms. F attended a Pro-Seminar conference in September 2012, where she saw Olsthoorn give a slide presentation about the Strictrade Offering to a group of 50 people.

[52] Ms. F decided to purchase $50,000 in licences under the Strictrade Offering as a way of generating money for herself in retirement. She testified that she would not have bought it had she not thought it would be profitable. She reviewed the slides, visited the website and asked Olsthoorn questions. She consulted with her accountant who advised her about tax deductions that could relate to the Strictrade Offering.

[53] Ms. F paid $7,500 in upfront fees and interest in December 2012. She signed all the agreements, dealing with Allen and Judy Smyth, an employee of TAL. In July of 2014, Ms. F purchased an additional $50,000 licence, requiring an additional annual upfront payment of $7,500 per year. The second licence was sold two months after the Respondents advised Staff of the Commission that they had voluntarily suspended the sale of the Strictrade Offering.

[54] Ms. F described the Strictrade Offering as a business, but one that she would not have to run herself. She did not see the Strictrade software in operation or use the Strictrade software. Ms. O believed that STL was the professional trading manager who either found customers for her or purchased the trading instructions at the predetermined price. The licence was an asset that she was purchasing for "someone" to use. Ms. F has continued to make her annual payments and treats the licence as a business asset for tax purposes.

5. Edna K

[55] Edna K testified that she and her husband, Warren K, run a business purchasing and renting residential properties, along with a home-building business. She is a former mutual fund and life insurance sales licensee. In 2012, Olsthoorn made a Strictrade presentation at the office of a "tax shelter" person, who was known to Ms. K.

[56] Ms. K and her husband wanted to offset their income for 2012 to pay less tax. She also hoped that the Strictrade Offering would be profitable, although she could not recall the details of the Software Performance Bonus. She testified that she found the Strictrade Offering complicated and met with Olsthoorn a second time to ask questions and make sure that she and her husband could take tax deductions from the Offering in 2012. Although her accountant advised caution, she and her husband decided to proceed.

[57] Ms. K received a one-page marketing document that described the Strictrade Offering as a "self-sustaining business in a box," which she understood as saying that the business would pay for itself. Although she signed a sub-distributor agreement and received a commission for her own and her husband's licence purchase, Ms. K did not intend to become a distributor, as she found it "too complicated to offer to any other people." She understood it as a business that somebody else ran for you and in which she and her husband did not have to do any of the work involved.

[58] Ms. K and Mr. K bought a $100,000 licence each and made their first payment of $30,000 for the total first year's fees and interest. Ms. K did not understand how the Strictrade software worked, who was using it and what was being traded. When she received the Trading Report Summary, she recalled that the income was what she expected.

[59] Ms. K and Mr. K terminated their involvement after the first year. Their deduction was denied because they had not owned it for long enough to take the deduction. Under the terms of the agreement, Ms. K and Mr. K had to wait three years to receive their trading report payments. They each received a $9,500 cheque in 2016 for these payments, a total of $19,000 paid to them as a result of their involvement in the Strictrade Offering.

E. STL and the Use of the Trading Software

[60] In the STL Services Agreement entered into with each purchaser, STL agreed as follows:

7.3 Notwithstanding any other term of this Agreement, STL shall commence trading Contracts on its own account as of the Effective Date provided STL has received Trading Instructions, unless this Agreement is terminated.

[61] The first STL Services Agreement was entered into in June 2012 (Mr. D), followed by six more in December of 2012 (Mr. G, Ms. O and Moira O, Ms. K and Mr. K and Olsthoorn, one of the Respondents). However, difficulties in opening a brokerage account, apparently due to civil proceedings involving Furtak, Olsthoorn and companies connected to them as defendants, meant that STL did not have the ability to trade until November 2013, contrary to section 7.3 of the STL Services Agreement.

[62] Ultimately, when the brokerage account was opened in November of 2013, Axton provided funding for trading through a loan to STL. The loan agreement, which Furtak signed on behalf of Axton and STL, permitted loans of up to 5 million USD from Axton to STL for "investment purposes." On October 30, 2013, Axton transferred $44,000 from its account to STL's account, which STL in turn transferred to the brokerage account.

[63] By August 2014, all of the trading capital in the STL brokerage account was lost or spent on fees and commissions. In November 2014, additional funds were provided from SMI and Axton to STL, which were wired to the brokerage account.

III. ISSUES AND ANALYSIS

[64] The Respondents submit that the Strictrade Offering was a set of contracts that created a business, not a security. They argue that the Strictrade Offering falls outside the jurisdiction of the Act. Staff submits that the Strictrade Offering was an investment contract and thus is a security within the meaning of subparagraph 1(1)(n) the Act. Given that the rest of the allegations turn on whether or not the Strictrade Offering is a security, we consider that question first.

A. The Preliminary Issue: Did the Strictrade Offering Involve an Investment Contract?

1. The Test and the Principles

[65] The Act sets out a number of documents, agreements, certificates and other contracts that are defined as securities. Subparagraph 1(1)(n) includes "any investment contract." This term is not further defined in the legislation but has been the subject of substantial consideration by courts in Canada and the United States, as well as the Commission.

[66] Counsel agree that the leading test for "investment contract" in Canada is articulated in Pacific Coast Coin Exchange v Ontario Securities Commission, [1978] 2 SCR 112. These elements can be described as:

1. an investment of money,

2. with an intention or an expectation of profit,

3. in a common enterprise in which the fortunes of the investor are interwoven with and dependent upon the efforts and success of those seeking the investment or of third parties,

4. whether the efforts made by those other than the investor are the undeniably significant ones -- essential managerial efforts which affect the failure or success of the enterprise.

[67] The courts apply these elements to a given set of facts in the context of the purposes of the Act, which include the protection of the investing public. In Pacific Coast Coin, the Supreme Court of Canada considered substance over form as well as the economic realities of the enterprise (at 127).

[68] The Supreme Court in Pacific Coast Coin referred to State of Hawaii, Commissioner of Securities v Hawaii Market Center, Inc., 485 P 2d 105 (1971), in which the Supreme Court of Hawaii articulated the risk capital approach to the definition of "investment contract":

The salient feature of securities sales is the public solicitation of venture capital to be used in a business enterprise. ... This subjection of the investor's money to the risks of an enterprise over which he exercises no managerial control is the basic economic reality of a security transaction.

(at 109)

[69] Cases that have applied Pacific Coast Coin in subsequent years have involved schemes that related to trading in accounts held by promoters who argued that their fundraising efforts were not sales of securities. In MP Global Financial Ltd. (Re) (2011), 34 OSCB 8897, the respondents raised funds from investors by selling debentures. The funds were to be used for forex trading, although the investors did not participate in the trading themselves. Investors received a flat interest rate regardless of the generation of profit. The respondents in MP Global argued that the investors did not share the risk and that the investors' fortunes were not "interwoven with and dependent upon the efforts and success of those seeking the investment or of third parties." The Commission disagreed, finding that the debentures were investment contracts because the trading efforts were the underpinning of the scheme and the potential for profit was dependent on the success of the respondents at trading in foreign currency.

[70] Investment contracts have been found in Canadian and US cases in arrangements as diverse as:

a. investments in solar panels and small plots of land in England (Energy Syndications Inc. (Re) (2013), 36 OSCB 6500);

b. proprietary software that would generate profits based on volatility (Axcess Automation LLC (Re) (2012), 35 OSCB 9019);

c. fractional interests in death benefits of life insurance policies (Universal Settlements International Inc. (Re) (2006), 29 OSCB 7880);

d. payphones (SEC v Edwards, 540 US 389 (2004));

e. dental devices sold by the promoter under sales agency agreements (SEC v Aqua-Sonic Products Corp., 687 F 2d 577 (2d Cir 1982)); and

f. an agreement to share in the ownership and revenue from blood alcohol testing machines in taverns (R v Ausmus, [1976] 5 WWR 105).

[71] In these cases, the promoters of the schemes had to do what was necessary to generate profits of the common enterprise that was the subject of contractual obligations among the parties. It did not matter whether there were fixed or variable returns (Edwards) or whether the investors had other opportunities to work with the underlying asset, where that was an unrealistic option (Energy Syndications; Aqua-Sonic).

B. The Application of the Test to the Strictrade Offering

[72] Staff argues that all four elements of the Pacific Coast Coin test apply to the Strictrade Offering. It submits that this is a classic example of an investment contract in that it was a package of agreements in which the investors were "entirely passive providers of capital, who funded an enterprise which was run entirely by the Respondents." Its structure as a licencing agreement does not insulate it from the substantive reality nor does its description by the promoters and some of the participants as a "business" and not an "investment." In identifying the issuer of the securities, Staff argues that the issuer consists of the parties to the key contracts, namely Axton and STL, and that the totality of these contractual arrangements constitutes the security in question.

[73] The Respondents submit that none of the elements of the Pacific Coast Coin test apply. The Respondents also urge the Commission to consider a different articulation of the Pacific Coast Coin test that would be easier to apply by business owners who may wish to consider whether or not a given scheme falls within the definition of an investment contract. They argue that this would avoid the potential for an overbroad application of the Act to legitimate business enterprises, which Laskin CJC cautioned against in his dissent in Pacific Coast Coin:

It is easy, in a case like the present one, when faced with a widely-approved regulatory statute embodying a policy of protection of the investing public against fraudulent or beguilingly misleading investment schemes, attractively packaged, to give broad undefined terms a broad meaning so as to bring doubtful schemes within the regulatory authority. Yet if the Legislature, in an area as managed and controlled as security trading has deliberately chosen not to define a term which, admittedly, embraces different kinds of transactions, of which some are innocent, and prefers to rest on generality, I see no reason of policy why Courts should be oversolicitous in resolving doubt in enlargement of the scope of the statutory control.

(at 117)

[74] The Respondents' alternative test has four questions:

1. How well does the form of business or investment relationship match the substance? Is there a business purpose to the business form?

2. Can the independent action of the party to the contract that is a putative investor materially affect its own commercial outcome?

3. Is the vulnerability of the putative investor solely attributable to the need for the other party to remain solvent in order to perform its obligations?

4. How are the purchasers approached?

[75] Counsel for the Respondents urges us to equate these policy questions to the test in Pacific Coast Coin and consider them as a preferred articulation of the test for a "business citizen." We considered this submission and have concluded that while some of these questions might well be relevant to the test, they cannot be meaningfully substituted for the Pacific Coast Coin test without changing the analysis in a way that the law does not contemplate. The policy questions would need to be asked within the framework set in place by the Supreme Court of Canada and applied in the numerous subsequent cases since Pacific Coast Coin was decided.

C. Application of the Pacific Coast Coin Test

1. Investment of Money

[76] Staff submits that the fact that investors paid money to the Respondents for the Strictrade Offering, by writing a cheque to SMI for the first year's interest and loan maintenance fees and the hosting fee owed to STL under the STL Services Agreement, equates to a finding that the investors invested money, a total of $513,000.00 in interest and fees, and that this represents the "investment of money."

[77] The Respondents argue that there was no "investment of money," but rather there was an agreement to purchase a limited use software licence at a fair market value, which could also be used to trade in the futures markets by the purchasers. They focus on the purposes for the "investment of money" versus the action of purchasers putting money into an enterprise.

[78] A plain reading of Pacific Coast Coin and other cases favour the straightforward question: Was there a payment? The purpose of the payment and aspects of the economic arrangements are addressed in the other elements of the test. In Pacific Coast Coin, the money was for purchases of silver coins, on margin or for cash. In Hawaii, purchasers paid money to become members of a store and were responsible for recruiting other members to buy interests in the store. In the Strictrade Offering, purchasers paid money for software licences. This part of the test is met because there was an investment of money.

2. With the Intention or Expectation of Profit

[79] Staff submits that the evidence of the investors demonstrates that each had an expectation of profit. Mr. G thought the Strictrade Offering would generate a profit he was not getting from his RRSPs, Ms. F believed she could earn "retirement income" and Ms. O testified, "I wanted to make some money if I could."

[80] The marketing materials emphasized the ability to reap "predictable after tax profits" from the Strictrade Offering in three ways: trading report payments, the Software Performance Bonus and tax deductions from the fees paid and depreciation of the software.

[81] The Respondents submit the case law is conflicting on whether or not the expectation of tax benefits forms part of the expectation of profit for purposes of the investment contract test. They point to cases that go both ways (Kolibash v Sagittarius Recording Co., 626 F Supp 1173 (1986) and Sunshine Kitchens v Alanthus Corporation, 403 F Supp 719 (1975)) for the proposition that not all schemes will include tax benefits as part of the expected profits. Kolibash involved marketing in which the tax benefits represented a substantial inducement to enter into the contract. Sunshine Kitchens involved two counterparties where the complaining counterparty had specific expectations of the tax benefits that were personal to that counterparty.

[82] In Kustom Design Financial Services Inc. (Re), 2010 ABASC 179, a decision of the Alberta Securities Commission, profit was found to include "all types of economic return, financial benefit or gain." The program in that case created a risk of financial loss, but this was sold as an overall benefit arising from potential tax advantages.

[83] The Kustom Design reasoning is applicable here given that the creation of the scheme, its marketing and the understanding of the various investors included the promise of profits that turned on the ability to secure favourable tax treatment by claiming expenses and depreciation. The model outlined in the Strictrade Offering meant that investors did not see a positive return unless they continued in the program for at least five years, at which point they would realize a small annual return on a completely unsecured investment only if they received the Performance Bonus. Thus, the only potential and meaningful "profits" from the Strictrade Offering were those resulting from tax deductions and depreciation.

[84] We prefer the reasoning in both Kolibash and Kustom Design in applying this part of the test. The marketing of the Strictrade Offering emphasized the role of tax benefits in profit to the participants, both in writing and during their evidence. The Respondents emphasized the need for participants to file a tax return. This was part of the expectation of profit on both sides of the transactions.

3. A Common Interwoven Enterprise with Passive Investors -- Success is Dependent on the Effort of Others

[85] Staff argues that all of the investors were passive participants. None of them saw, used or received the trading software. None of the investors believed they had the knowledge to run the software. The presentations were consistent with this as well, including the slide that contained the representations that participants were insulated from any operations, the business required only an annual tax filing and the software required "no personal expertise whatsoever." Although a participant could have theoretically used the trading software, in reality, that was not the package sold to any participant, and none of them testified that they could have operated the software or were interested in doing so.

[86] The ability of the investors to earn any returns depended wholly on the companies set up by Furtak who were the counterparties to the various agreements. The obligation to pay the trading report payments and the Bonus fell with STL. STL lost money in its use of the trading software (taking into account both trading and liabilities in connection with the offering of the licences) and required intercompany loans from other companies owned and controlled by Furtak, including Axton. The returns to the licensees were based on unsecured promises from STL to pay, which in practice had to be supported by loans from other companies controlled by Furtak. Such support could have been withdrawn by Furtak at any time.

[87] Thus, the issuers of the investment contract consisted of Axton and STL. These companies provided the key contractual attributes of this common enterprise, and the investors were legally dependent on them for their promised returns.

[88] In contrast, the Respondents operated the technical, administrative and financial aspects of the enterprise, including:

a. hosting and operating the trading software;

b. monitoring the internet connection to access real time market data;

c. connecting additional software to serve as the interface between the Strictrade software and the brokerage account;

d. opening and funding a brokerage account;

e. generating the trading instructions to the participants;

f. making payments to the participants;

g. moving money from various corporate entities to enable the payments to the participants;

h. sending anniversary notices to the participants to ensure they made their annual payments; and

i. processing early terminations of participation.

[89] The Respondents argue that in the Strictrade Offering, the licensees were not merely passive investors. They said that participants controlled the number of licences purchased, the timing of the purchase, the decision to continue to stay in the scheme and when and how to claim their tax deductions. These actions can fairly be said to be a function of virtually any type of investment and are personal to each participant. None of these actions, taken individually, involved running the business at the heart of the Strictrade Offering. They are consistent with the choices and decisions made by a passive investor when purchasing any financial instrument (equity, bond, mutual fund) and are not, on their own, evidence of significant involvement in the "business" of the Strictrade Offering.

[90] Furthermore, the Respondents submit that the Panel ought to consider the impact a finding that the Strictrade Offering was a security may have on taxpayers. The fact that another body of law such as the Income Tax Act, in furthering other governmental objectives, allows for elections of this kind by a taxpayer and may characterize the licence as a business asset in determining the availability of these elections is not relevant to whether these arrangements constitute a "security" for purposes of the Act.

[91] We conclude that all of the elements of the Pacific Coast Coin test have been met by the evidence on a balance of probabilities. The investors were completely dependent on the promoters for the success of the enterprise, paid money into the enterprise and had an expectation of profit. The Strictrade Offering was an investment contract and was a security within the meaning of the Act. In conducting this analysis, we considered the third and fourth elements of the investment contract test together, as has been done in other decisions.

[92] The Respondents' final submission asked the Commission to find that the Strictrade Offering was not an investment contract due to the lack of any misconduct by the Respondents in marketing and creating the Offering. The Respondents characterize themselves as responsible promoters. They argue that this feature should "tip the scale" in favour of finding no investment contract in this case and that this application of the rule is in line with the caution articulated by Laskin CJC in his dissent in Pacific Coast Coin.

[93] Even if responsible promoter conduct is relevant to the investment contract test in Pacific Coast Coin, the evidence here does not support such a finding. The Strictrade Offering was a non-arm's length group of companies selling software licences of uncertain value. The scheme was marketed to participants in a way that made the structure and "business" operations difficult to understand. The slides used at the various presentations implied that there were profits, revenues and money involved. In one presentation, every slide contained an image of a puzzle piece with a dollar sign on it. Phrases, such as "Profit from Volatility in the markets," "Less than 15% of Managers and Brokers Beat the S&P Index" and "Equity Management Program Turn Strategies On and Off To Maximize Profits" suggest attractive returns from the Strictrade investment.

[94] The evidence establishes that the Respondents created a complicated structure that was not well understood by potential purchasers. The structure included an agreement for Axton to "loan" money to investors even though Axton actually did not have to provide any capital. There was no logical link between the amount of capital specified that could be used per licence to any actual trading leverage related to the STL trading account. Further, the use of the trading software produced the same trade reports for each licence holder. Thus, the "selling" of multiple licences, which produced the same reports to purchasers, enabled Axton and STL to have use of the licensees' capital for one year before any "trade report" payments were made.

[95] Participants did not understand that the deal promised little in the way of before tax profits or an independent source of income for the purchasers. Mr. G and Ms. O were surprised to find out that although the Strictrade Offering was described as "self-financing," they were required to make annual payments beyond the initial payment. Mr. G misunderstood that he was financing the purchase of the asset. The marketing materials, both the slides and the website, referred to the valuation of a differently structured licence to lend credibility and evidence of "intrinsic value" to this licence. This was misleading.

[96] Overall, we decline to find that this was a responsible business arrangement caught by an overbroad definition of investment contract. The Strictrade Offering has more in common with the type of investments described by Laskin CJC as "beguilingly misleading investment schemes, attractively packaged."

[97] In their submissions, the Respondents refer to Canadian and US case law that sets the framework for defining an "investment contract." They argue that "these broad tests are meant to catch novel avoidance schemes." The evidence in this case establishes that the Strictrade Offering was such a scheme.

[98] Having found that the Strictrade Offering was a security, it is necessary to consider the balance of the allegations and the evidence in support of those allegations.

D. Subsection 25(1): Did Furtak, Axton, STL, Allen and SMI Engage in the Business of Trading without Being Registered?

[99] The Act requires registration to ensure that those who engage in trading securities are solvent, knowledgeable and have the necessary integrity to properly deal with investors (Limelight Entertainment Inc. (Re) (2008), 31 OSCB 1727 at para 135). Registration is a key feature of the investor protection provisions within the Act.

[100] Furtak, Axton, STL, Allen and SMI were neither registered nor exempt from being registered. Each of them engaged in activities that meet the definition of trading as defined in the Act. Furtak, Axton and STL prepared and signed the License, Credit and Services Agreements, marketed and sold the Strictrade Offering, used and directed investor funds and made trading report payments.

[101] SMI and Allen marketed and sold the Strictrade Offering to investors by arranging meetings with professionals, conducting public Pro-Seminars and handing out brochures. SMI and Allen sent out packages of signed agreements, annual renewal letters and trading report summaries. These activities were not those of a bona fide start-up business that, of necessity, must seek out additional funds to operate its business, as was the case in Future Solar Development Inc. (Re) (2016), 39 OSCB 4495. Instead, the Strictrade Offering involved the use of pre-existing software sought to be monetized by a salesforce that was motivated by the opportunity to earn commissions from the sale of securities.

[102] We find that the Respondents engaged in the business of trading securities, in the form of the Strictrade Offering. They formed companies to market and sell the Strictrade Offering to members of the public. They used a website, slides and brochures. They held numerous presentations to small and larger groups across Canada and in Las Vegas, United States. SMI was created to market the Strictrade offering. The active solicitation by Allen, the creation of the structure by Furtak and the role of the corporate entities in carrying out the Strictrade Offering were all features of the business of selling this security to the public.

[103] The Respondents have not relied on any exemption from registration, and there was no evidence tendered of any exemption. We find that the Respondents Furtak, Axton, STL, Allen and SMI breached subsection 25(1) of the Act.

E. Subsection 53(1): Did the Respondents Distribute a Security without Filing a Prospectus as Required?

[104] The prospectus requirement in the Act is another important aspect of investor protection. The receipt of prospectuses by the Commission to ensure compliance with disclosure to potential investors in accordance with the Act and regulations provides another layer of oversight in the market. Subsection 53(1) requires securities that have not previously been distributed to include a preliminary prospectus and a prospectus filed and receipted by the Director.

[105] Counsel for the Respondents submits that TAL was not involved in the Strictrade Offering; this was the reason for incorporating SMI, which had an agreement in place setting out its role in marketing the Strictrade Offering. In contrast, there was no such agreement in place for TAL. However, in the absence of any formal arrangement, TAL was an active participant in the Strictrade Offering. TAL provided administrative and bookkeeping services for the Offering through a TAL employee, acted as the funder of Allen's marketing services by making payments to Allen's numbered company, paid expenses for Olsthoorn's travel to present the Strictrade Offering, provided a database of contacts to whom Olsthoorn marketed the Strictrade Offering and allowed Olsthoorn to hold himself out as a TAL executive in his investor presentations.

[106] We find that in carrying out the various activities used to assist with the marketing of the Strictrade Offering, TAL acted in furtherance of trades.

[107] The Respondents acknowledged that no prospectus was filed, given their position that the Strictrade Offering was not a security. Having found that it was a security, the Respondents breached subsection 53(1) of the Act in distributing the Strictrade Offering without having filed a prospectus.

F. Subsection 44(2): Did Furtak and STL Make a Misrepresentation to the Investors in the STL Services Agreement?

[108] Staff alleged that Furtak and STL misrepresented to each investor that STL would begin trading using the software on the effective date of the agreement as signed. In fact, when the agreements were signed, there was no brokerage account yet opened, and it took months before it was opened and in place. Staff submits that this information would be relevant to a reasonable investor in deciding whether to enter into or maintain a trading relationship with Furtak and STL.

[109] Furtak testified that this was not a concern because the trading report payments were accounted for and made as if the trading had begun on the effective dates. The Respondents argue that this was not a misrepresentation but rather a failure to abide by the term of a contract.

[110] The term of each agreement that is alleged to be a misrepresentation reads:

7.3 Notwithstanding any other term of this Agreement, STL shall commence trading Contracts on its own account as of the Effective Date provided STL has received Trading Instructions, unless this Agreement is terminated.

[111] In addition to this term, there was a second term in the agreements that referred to the timing of the start of trading. Section 7.2 reads:

7.2 STL shall as soon as commercially practicable after the Effective Date, and subject to any trading capacity restrictions on the License, use the Trading Instructions to commence trading Contracts for its own account. STL shall, in its sole discretion, have the right to determine, within the limits of the License, the allocation and to set the quantum and level of margin (i.e., cash) and trading leverage in STL's Trading Account.

[112] Subsection 44(2) of the Act reads:

No person or company shall make a statement about any matter that a reasonable investor would consider relevant in deciding whether to enter into or maintain a trading or advising relationship with the person or company if the statement is untrue or omits information necessary to prevent the statement from being false or misleading in the circumstances in which it is made.

[113] Untrue statements have been found to breach this provision in circumstances where promoters included misleading, unsupported or inaccurate marketing materials to investors. In this case, Staff relies on the provisions of the contracts rather than the marketing information to support a finding of misrepresentation. The Respondents submit that a contractual term is not a statement and that a failure to comply would have remedies in contract. They also submit that sections 7.2 and 7.3, read together, are ambiguous as to the requirements of when the trading had to occur. Finally, given that the licensees had already decided to enter into the agreements, it could not be said that this term was relevant to their decision.

[114] A reasonable investor might well wonder why they were to receive payments for trading when their "customer" STL was neither trading until many months later nor generating any profits. The business motivations of the promoters in obtaining the funds, rather than the trading software (which they did not actually need participants to obtain since the software was controlled by Furtak), would have been highly relevant to an understanding of the nature of the scheme. The trade start delay would therefore be considered relevant. Certainly, it was to Ms. O, Mr. G and Ms. F, who all believed that the trading would begin right away. However, is section 7.3 of the agreement an untrue statement prohibited by subsection 44(2)?

[115] We agree with the Respondents that the terms of section 7.3 are an obligation rather than a representation. The relevant phrase is, "STL shall commence trading Contracts on its own account as of the Effective Date provided STL has received Trading Instructions." However, the wording in section 7.2, "as soon as commercially practicable," leaves the impression that there could be some leeway regarding the starting date for using the trading instructions. It is unclear why section 7.2 is included given that section 7.3 begins with "Notwithstanding any other term of this Agreement ... ." These provisions describe STL's obligations. They do not constitute marketing or promotional materials intended to persuade investors to participate. The wording is not a clear inducement, and the combined impact of sections 7.2 and 7.3 creates some ambiguity.

[116] Accordingly, although there might well be situations where the nature of a contract or an agreement amounts to a misrepresentation under subsection 44(2), we decline to make such a finding on the facts in this case. The allegations under subsection 44(2) against Furtak and STL are dismissed.

G. Did Olsthoorn and TAL Fail to Meet their Obligations as Registrants?

[117] The Respondents TAL and Olsthoorn did not challenge the evidence that they did not meet their KYC, Know Your Product (KYP) or suitability obligations. We have found that the Strictrade Offering was a security and that TAL was involved in its distribution. Neither Olsthoorn nor TAL discharged their obligations, as set out in subsection 13.2(2) and section 13.3 of NI 31-103. As a registrant, Olsthoorn had an obligation in dealing with clients or potential clients to consider whether the investment was suitable for that individual, given his or her financial circumstances.

[118] In particular, Olsthoorn recommended to investors that they withdraw money from existing RRSPs to make their investments, suggesting that their earnings from Strictrade could earn more than the tax consequences of an RRSP withdrawal. One investor, Mr. G, withdrew funds from his RRSP and made payments to Strictrade amounting to more than 60% of his annual income. We accept Staff's submissions that the Strictrade Offering was unsuitable for this investor and that Olsthoorn failed to collect the necessary information. Rather, Olsthoorn told Mr. G that the Strictrade Offering would perform better than his RRSP and that there was little to no risk in using his funds to purchase the Offering.

[119] Olsthoorn testified that he suggested to investors that they speak with their accountants; however, this does not permit him to delegate his responsibility to satisfy suitability criteria, under section 13.3 of NI 31-103. As the seller of the product, which investors described as difficult to understand, Olsthoorn bore the responsibility of determining its suitability for the potential purchasers.

[120] The KYC and suitability obligations in the Act require reasonable steps to ensure a registrant has sufficient information about investors, including investment needs and objectives, the client's financial circumstances and the client's risk tolerance. Olsthoorn testified that he refrained from collecting this information given his belief that the Strictrade Offering was not a security. In this sense, he preferred his own legal interests over the financial interests of the participants. Further, his lack of understanding of the features and nature of the Offering meant that he failed in his KYP obligations. This revealed a lack of proficiency and a failure of this obligation as required under NI 31-103.

H. Olsthoorn's UDP and CCO Obligations

[121] Olsthoorn, as the UDP and CCO of TAL, was required to:

"Establish and maintain policies and procedures for assessing TAL's compliance with securities legislation, monitor and assess compliance by TAL and individuals acting on TAL's behalf"

and

"Supervise the activities of TAL that were directed towards ensuring compliance with securities legislation, and to promote compliance by TAL and individuals acting on TAL's behalf with securities legislation."

[122] Olsthoorn failed to carry out these obligations in relation to TAL's involvement in the Strictrade Offering. We find that these allegations have been made out.

I. Did Furtak, Allen and Olsthoorn Authorize, Permit or Acquiesce in Non-compliance by their Companies of Securities Laws, Contrary to Section 129.2 of the Act?

[123] Furtak as an officer of Axton and STL, Allen as an officer and director of SMI and Olsthoorn as an officer and director of TAL, each authorized, permitted or acquiesced in their companies' non-compliance with Ontario securities laws. As a result, the allegations under section 129.2 of the Act have been made out on a balance of probabilities.

IV. PUBLIC INTEREST MANDATE: REMEDIAL PROVISIONS OF SECTION 127 OF THE ACT

[124] For the reasons stated above, we find that during the Material time:

a. Allen, SMI, Furtak, Axton and STL engaged in, or held themselves out as engaging in, the business of trading in securities without registration, contrary to subsection 25(1) of the Act;

b. all of the Respondents distributed securities when a preliminary prospectus and a prospectus had not been filed and a receipt had not been issued by the Director, contrary to subsection 53(1) of the Act;

c. Olsthoorn and TAL:

i. failed to discharge their KYP obligation in respect of the Strictrade Offering and therefore breached their suitability obligations under sections 3.4 and 13.3 of NI 31-103; and

ii. failed to take reasonable steps to collect sufficient information to determine whether the Strictrade Offering was suitable for investors, breaching their KYC and suitability obligations under sections 13.2 and 13.3 of NI 31-103;

d. Olsthoorn, as CCO and UDP of TAL:

i. failed to fulfill his obligations as UDP of TAL to supervise the activities of TAL in order to ensure compliance with securities legislation by TAL and individuals acting on its behalf, and to promote compliance with securities legislation, contrary to section 5.1 of NI 31-103; and

ii. failed to fulfill his obligations as CCO of TAL to monitor and assess compliance by TAL and individuals acting on its behalf with securities legislation, contrary to section 5.2 of NI 31-103;

e. Furtak, Olsthoorn and Allen, as directors and officers of Axton and STL (Furtak), TAL (Olsthoorn) and SMI (Allen) (the Corporate Respondents), authorized, permitted or acquiesced in the Corporate Respondents' non-compliance with Ontario securities law, and accordingly are deemed to have failed to comply with Ontario securities law, pursuant to section 129.2 of the Act; and

f. the Respondents engaged in conduct contrary to the public interest.

[125] Section 127 of the Act permits the Commission to make orders where conduct is contrary to the public interest and harmful to the integrity of capital markets. A number of remedial options are available to the Commission to meet the protective and preventative purposes of the Act.

[126] We find that the public interest mandate of the Commission has been engaged by the evidence heard in this matter. Staff shall contact the Commission's Office of the Secretary, copying all parties, within 15 days of these Reasons and Decision to arrange dates for a hearing regarding sanctions.

Dated at Toronto this 24th day of November, 2016.

{1} RSO 1990, c S.5.

{2} A diagram representing the Strictrade Offering is contained in Appendix A of these reasons.

{3} The evidence was not entirely clear on this point; however we have assumed the payment of the fifth year is included in the bonus calculation, as this is the most favourable interpretation to the Respondents.

APPENDIX A

THE STRICTRADE OFFERING